This is a story of nostalgia, retro-computing, gaming, reverse-engineering, and fixing a decades-old bug. It might be a bit long, and can get rather technical in places (a lot of places), but if you’re into that sort of thing, I think you may find it enjoyable.

The Game

When I was a kid, my family had a Commodore 128 (C128) computer. The C128 was the successor to the famous Commodore 64 (C64), and it could be booted into a C64-compatible mode. I used this computer all the time, for playing games, writing papers for school, and, of course, programming. Probably most of my time on the computer was spent playing games. One of my favorites was a game called B.C.’s Quest for Tires. It’s a pretty simple side-scrolling game in which the player moves steadily to the right, and has to jump and duck obstacles to proceed.

I had, and still have, a copy (of dubious provenance) of the C64 version of the game on a floppy disk. A couple of years ago, I used a ZoomFloppy with my Commodore 1571 disk drive to make images of many of my old Commodore disks, including the one containing Quest for Tires. I loaded the game up in the VICE emulator and started playing, but the nostalgia I felt was quickly and rudely interrupted when the game crashed.

One of the things the player can do in the game is to change the main character’s speed, with a minimum speed of 10 and a maximum of 80. Partway through the game, the minimum speed is increased to 40. (There are no units specified, but I assume it’s meant to be in miles per hour.) The faster you go, the more difficult the game is, but the more points you get along the way. Unfortunately, every time I got the speed up to 80, the game crashed. Everything else seemed to work fine, so I just kept my speed below 80, but it was annoying that the game crashed at all.

A few days ago, I was re-watching 8-Bit Show and Tell‘s YouTube video about fixing an old bug in the C64 version of Pac-Man, and I was inspired to see if I could resolve the mystery of the Quest for Tires crash, and possibly even fix it. (As an aside, if you have any interest in retro-computing in general, and Commodore computers in particular, you should definitely check out that channel. Right now. I’ll be here when you get back.)

Finding the Bug

To figure out what’s going on, let’s use VICE’s built-in machine language monitor, which is a debugging tool that can examine and modify code and data in the machine’s memory. Some reference material to keep handy will be:

- Joe Forster‘s Commodore 64 memory map

- Michael Steil‘s Ultimate Commodore 64 Reference, especially the C64 KERNAL API section

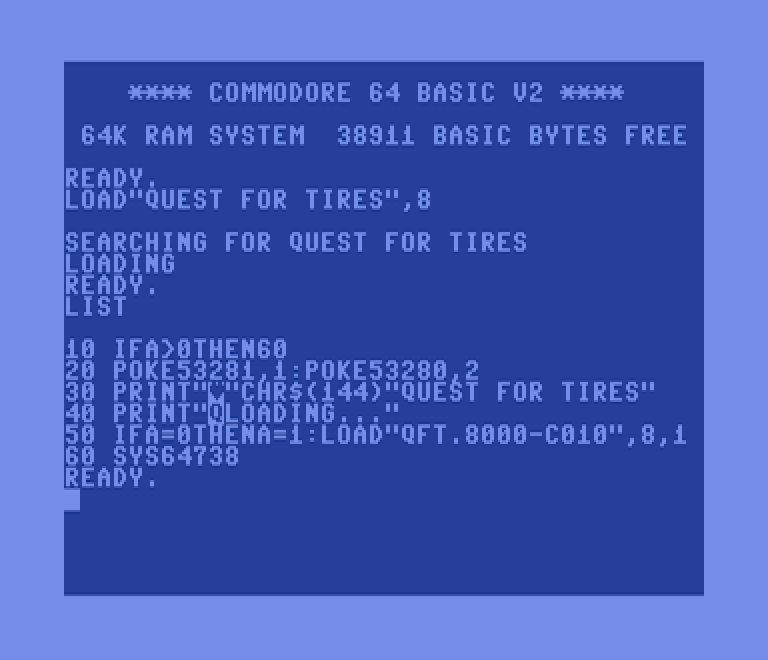

The game on disk consists of two files: "QUEST FOR TIRES", which is a short BASIC program that loads and executes the second file, "QFT.8000-C010", which is the machine code for the game itself. Based on the filename, it seems pretty likely that the machine code gets loaded to the addresses $8000 through $C010. (Note: the convention with 6502-based computers, like the C64, is to represent hexadecimal numbers like addresses with a leading $, and binary numbers with a leading %.)

Since the crash is clearly related to changing the player’s speed, a good place to start might be to look for the code that updates the speed. To change the character’s speed, the player presses and holds the joystick button and moves the joystick left (to slow down) or right (to speed up), so we should look for instructions that read and process the joystick state.

Using the Monitor

VICE’s machine language monitor, when active, pauses the computer and presents a prompt where the user can enter commands to examine or modify the state of the computer, or to resume normal execution. Here’s a summary of the monitor commands we’ll be using, with abbreviations where applicable:

- a – assemble instructions into memory

- backtrace (bt) – display the chain of subroutine calls leading to the current instruction

- bank – control which devices and memory ranges are visible in the monitor

- break (bk) – set a breakpoint on a memory location

- disass (d) – disassemble the contents of a memory range

- goto (g) – resume execution, optionally jumping to a new location

- hunt (h) – search through a memory range for a byte sequence

- load (l) – load a file from disk into memory

- mem (m) – display raw contents of a memory range

- next (n) – execute a single instruction, stepping over subroutine calls

- save (s) – save a region of memory to a file on disk

- step (z) – execute a single instruction, stepping into subroutine calls

Reading the Joystick

On the C64, the state of joystick port #1 can be read from memory address $DC01, and the state of joystick port #2 can be read from $DC00. The value read from the joystick port is encoded in the lowest five bits, and each bit is active low, so 0 if pressed and 1 if not pressed. The five bits from right to left are:

- Bit 0: joystick up

- Bit 1: joystick down

- Bit 2: joystick left

- Bit 3: joystick right

- Bit 4: fire button

For example, if the joystick is idle, the binary value read from the joystick port would be %00011111, or $1F in hexadecimal. If the joystick is pointed down and to the left, and the fire button is being pressed, the binary value read from the joystick port would be %00001001, or $09 in hexadecimal. (Actually, the top three bits will probably be different. They’re related to the state of the keyboard.)

The game is played with the joystick connected to port #2, so it must have some code somewhere to read from $DC00. Let’s see if we can find it.

Bank Switching

There’s one more thing we need to deal with before running our search—bank switching. The C64’s 6510 CPU has a 16-bit address bus, which means it can address a maximum of 64k (65,536) different memory locations. The C64 has a full 64k of RAM, but it also has ROMs and I/O devices that need to fit into the same address space, which the C64 handles by bank switching. This strategy involves mapping different devices into and out of the address space so that all of the memory and devices can be accessed, though not all at the same time.

The C64, by default, has a BASIC ROM mapped into the address range $A000–$BFFF, masking the RAM at those locations, which in our case will contain the second half of the game code. If a program writes to those addresses, the data will be written to the RAM. As a result, with the default bank setup, we can load the game into memory, but if we try to read that code, we’ll get the contents of the BASIC ROM instead.

Memory location $01 controls what devices are banked in and out, and location $00 controls writes to $01. (By convention, addresses less than $0100 are written with just two hex digits instead of four.) We could write to those addresses with the monitor to bank out the BASIC ROM. However, we can use the monitor’s bank command to read from the RAM without changing the computer’s state, so let’s stick to that approach, at least for now.

searching the code

Let’s load the machine code file into memory and search for instructions that refer to $DC00. The 6510 processor in the C64, like the 6502 it’s based on, uses little-endian byte ordering, so instead of searching for the byte sequence $DC $00, we’ll need to search for the sequence $00 $DC.

(C:$e5d4) l "qft.8000-c010" 8 Loading qft.8000-c010 from 8000 to C00F (4010 bytes) (C:$e5d4) bank ram (C:$e5d4) h 8000 c00f 00 dc a089 ad71

Great, we found two memory addresses which reference that address. Let’s disassemble and look at the code around the first one, $A089. To get some context about the code you’re looking at, a good tactic is to disassemble several bytes before and after the location of interest. So, let’s disassemble starting at $A07E and going through $A0A5:

(C:$e5d4) d a07e a0a5 .C:a07e AD 0F 12 LDA $120F .C:a081 D0 3C BNE $A0BF .C:a083 AD 5E 40 LDA $405E .C:a086 D0 37 BNE $A0BF .C:a088 AD 00 DC LDA $DC00 .C:a08b 29 10 AND #$10 .C:a08d F0 14 BEQ $A0A3 .C:a08f A5 C5 LDA $C5 .C:a091 C9 04 CMP #$04 .C:a093 F0 0E BEQ $A0A3 .C:a095 C9 06 CMP #$06 .C:a097 F0 07 BEQ $A0A0 .C:a099 C9 05 CMP #$05 .C:a09b D0 3F BNE $A0DC .C:a09d 4C 06 BF JMP $BF06 .C:a0a0 4C 30 BF JMP $BF30 .C:a0a3 EE 0F 12 INC $120F

We can see the instruction LDA $DC00 at address $A088. This instruction reads the value at address $DC00 (the joystick port) and loads it into the CPU’s accumulator register, also called the A register. The next two instructions, AND #$10 and BEQ $A0BF, check if the fire button is being pressed. However, none of the other joystick bits are being checked here, so it’s unlikely that this is in-game code. More likely, it’s part of code that runs at the “game over” screen, waiting for the player to press the fire button to start the next game.

Perhaps we’ll have better luck with the other address where we found the joystick port being accessed, $AD71. Again, let’s expand out a bit to get context, and disassemble $AD61 to $AD80.

(C:$a0a6) d ad61 ad80 .C:ad61 D0 AD BNE $AD10 .C:ad63 70 40 BVS $ADA5 .C:ad65 69 00 ADC #$00 .C:ad67 A2 00 LDX #$00 .C:ad69 20 13 B3 JSR $B313 .C:ad6c 4C 1C AD JMP $AD1C .C:ad6f 60 RTS .C:ad70 AD 00 DC LDA $DC00 .C:ad73 8D 3D 40 STA $403D .C:ad76 60 RTS .C:ad77 AD 39 40 LDA $4039 .C:ad7a C9 20 CMP #$20 .C:ad7c D0 03 BNE $AD81 .C:ad7e 4C F6 B2 JMP $B2F6

This is interesting. The LDA $DC00 instruction reads the value of the joystick port and the next instruction, STA $403D, stores that value into a memory address. Presumably, this is so that it can be read multiple times by the code without it potentially changing between reads. Let’s see how many places in the game code read that location. Let’s look for intances of the instruction LDA $403D, which assembles to the three-byte sequence $AD $3D $40. (If we don’t find much, we can expand the search to other instructions that use that address.)

(C:$ad81) h 8000 c00f ad 3d 40 9fd0 9fd7 9fde afee b001 b03d b044 b05b b14d b161

That instruction is found in ten different places in the code. Not a huge number, but not a small number either. Notice, however, that they seem kind of clustered into groups. This would make sense if we expect that the joystick state might be read multiple times in a subroutine. Let’s start going through them. To look at the first group of three, let’s disassemble and examine $9FC0 to $9FFD:

(C:$ad81) d 9fc0 9ffd .C:9fc0 18 CLC .C:9fc1 69 0F ADC #$0F .C:9fc3 8D 30 40 STA $4030 .C:9fc6 CE 25 40 DEC $4025 .C:9fc9 10 20 BPL $9FEB .C:9fcb A9 0A LDA #$0A .C:9fcd 8D 25 40 STA $4025 .C:9fd0 AD 3D 40 LDA $403D .C:9fd3 29 10 AND #$10 .C:9fd5 D0 14 BNE $9FEB .C:9fd7 AD 3D 40 LDA $403D .C:9fda 29 08 AND #$08 .C:9fdc F0 10 BEQ $9FEE .C:9fde AD 3D 40 LDA $403D .C:9fe1 29 04 AND #$04 .C:9fe3 D0 06 BNE $9FEB .C:9fe5 CE 61 40 DEC $4061 .C:9fe8 EE 24 40 INC $4024 .C:9feb 4C 03 A0 JMP $A003 .C:9fee EE 61 40 INC $4061 .C:9ff1 CE 24 40 DEC $4024 .C:9ff4 AD 24 40 LDA $4024 .C:9ff7 C9 04 CMP #$04 .C:9ff9 B0 08 BCS $A003 .C:9ffb 4C 00 A0 JMP $A000

This is very promising. The joystick state ($403D) is read three times, each time to check a different bit. The three bits checked are bit 4 ($10, fire button), bit 3 ($08, joystick right), and bit 2 ($04, joystick left). These are exactly the relevant bits for controlling the speed. The first check, at $9FD0, looks to see if the fire button is pressed, and if not, jumps ahead to $9FEB, which immediately jumps to $A003.

The next two checks only occur if the fire button is pressed. The second check, at $9FD7, looks to see if the joystick is pointing right (to speed up), and if it is, jumps ahead to $9FEE, which increments location $4061 and decrements location $4024. It then checks if the value stored at $4024 is less than 4. If it’s greater than or equal to 4, it jumps ahead to $A003, but if it’s less than 4, it jumps to $A000 instead.

If the second check doesn’t find the joystick pointing right, the code falls through to the third check, at $9FDE. This looks to see if the joystick is pointing left (to slow down), and if it’s not, jumps ahead to $9FBE, which as we’ve already seen, immediately jumps to $A003. If the joystick is pointing left, then $4061 is decremented, and $4024 is incremented, and then the code jumps to $A003.

This very much appears to be the subroutine that updates the speed based on player input. It seems like $A003 is the location to jump to when we’re done updating the speed, and $4061 and/or $4024 are good candidate locations for where some representation of the speed is stored. $4061 is incremented when the character speeds up and decremented when the character slows down, so that at least moves in the right direction. $4024 goes in the opposite direction, but it is compared against some kind of limit (4), which fits with the fact that the in-game speed is limited. Maybe they’re both different representations of the speed. Let’s look at the disassembly for $A000 to $A020 and see if we can learn anything more.

(C:$9ffe) d a000 a020 .C:a000 EE 24 40 INC $4024 .C:a003 AD 24 40 LDA $4024 .C:a006 CD 30 40 CMP $4030 .C:a009 90 06 BCC $A011 .C:a00b AD 30 40 LDA $4030 .C:a00e 8D 24 40 STA $4024 .C:a011 4A LSR A .C:a012 4A LSR A .C:a013 AC 1B 40 LDY $401B .C:a016 AE 1A 40 LDX $401A .C:a019 C0 07 CPY #$07 .C:a01b D0 04 BNE $A021 .C:a01d E0 95 CPX #$95 .C:a01f F0 0C BEQ $A02D

Let’s look at $A003 first, as it’s the target of several jump and branch instructions. This section of code loads the value at $4024 into the A register, then compares it to the value at $4030. If the value at $4024 is less than the value at $4030, the code jumps ahead to $A011. Otherwise, if the value at $4024 is greater than or equal to the value at $4030, the value at $4030 is copied into $4024, and the next instruction is at $A011. So, this seems to be setting an upper limit for $4024, with an adjustable limit value stored at $4030.

$A000 is the address jumped to when the value at $4024 is less than 4. This instruction increments $4024, and therefore enforces a hard-coded lower limit of 4 for this value. The next instruction is $A003, which, as we’ve just seen, contains the upper-limit code for the same location. Since $A000 has just enforced the lower limit, the upper-limit code will likely have nothing to do. After this, the code once again reaches $A011.

$A011 seems not to have much more to do with setting the speed, and likely just carries on with other game logic. Nevertheless, I think we’ve finally achieved our first milestone, which is to find the code which handles the speed. That is, after all, where the bug seems to be. In particular, the crash happens when the player accelerates past 80.

Stepping Through the Crash

The VICE monitor has the capability to set breakpoints, which stop the computer and open the monitor prompt when the breakpoint’s condition is satisfied. These conditions are usually something like “stop when execution reaches a certain address”, but they can also break on reading/writing memory locations, and can be restricted to break only when other memory locations have specific values. It’s a very powerful debugging tool, because while the computer is paused at a breakpoint, the user can examine and/or modify memory, and step execution forward one instruction at a time.

Since the crash we’re looking for happens when the player tries to speed up past the limit, and since instruction $9FFB is executed if and only if a limit is exceeded during a speed-up action, let’s do the following:

- start the game,

- break into the monitor,

- set a breakpoint at $9FFB,

- resume the game, and

- accelerate past 80.

Then, if/when our breakpoint is hit, we can trace through the code and see what might be causing the crash.

(C:$bf5e) bk 9ffb BREAK: 1 C:$9ffb (Stop on exec) (C:$bf5e) g #1 (Stop on exec 9ffb) 69/\5, 55/\ .C:9ffb 4C 00 A0 JMP $A000 - A:03 X:00 Y:00 SP:ff N.-..... 63751795

Nice, we hit our breakpoint, right when we expected to. Now let’s trace through the next few instructions to see if we can determine what’s going wrong.

(C:$9ffb) z .C:a000 55 24 EOR $24,X - A:03 X:00 Y:00 SP:ff N.-..... 63751798 (C:$a000) z .C:a002 40 RTI - A:03 X:00 Y:00 SP:ff ..-..... 63751802 (C:$a002)

That’s definitely very wrong. RTI is an instruction meant to return from an interrupt handler. Executing that when not in an interrupt handler is a good way to corrupt the stack and crash the computer. We have our smoking gun. But why is this instruction being executed? And why is $A000 now EOR $24,X instead of the INC $4024 we saw before? The three bytes starting at $A000 are currently $55 $24 $40. But before we started the game, they were $EE $24 $40, which disassembles to the expected INC $4024. Only the first byte is different. Somehow, the byte at $A000 is getting corrupted and breaking the code.

Understanding the Bug

The Source of the Corruption

As I mentioned, the breakpoints in VICE’s monitor are pretty powerful, and they can be set up to break when a specific memory location is written to. We can use that try to find the culprit. But there’s a small complication to deal with. We don’t want to break when loading the machine code into RAM. We only want to break when $A000 changes after that initial load.

So, instead of the typical LOAD"*",8 followed by RUN to start the game, we’re going to do things a bit more manually. First we’ll load the BASIC loader program to look and see what steps it takes to load and start the game. Then we’ll load the machine code into RAM ourselves, and then set our breakpoint. Finally, we’ll run the command from the loader program that actually starts the game.

The relevant lines of code for us are 50 and 60. The rest are boilerplate code to display a loading screen and handle some quirks when a BASIC program loads another program. Line 50 loads the machine code with LOAD"QFT.8000-C010",8,1. Line 60 then executes that code with SYS64738. SYS is a BASIC command that jumps to an address and starts executing the machine code there. BASIC doesn’t use hexadecimal, so the address is specified in decimal.

64,738 in decimal is $FCE2 in hexadecimal, which some readers may recognize as the address of the KERNAL routine to reset the computer (without clearing the RAM). The loader program apparently loads the machine code into RAM and then resets the computer, which somehow causes the game to start. We’ll revisit this a bit later. For now, we know what steps we need to take to set our breakpoint and find out what’s corrupting memory at address $A000. Let’s do that now.

(C:$e5cf) l "qft.8000-c010" 8 Loading qft.8000-c010 from 8000 to C00F (4010 bytes) (C:$e5cf) bk store a000 WATCH: 1 C:$a000 (Stop on store) (C:$e5cf) bank default (C:$e5cf) g fce2 #1 (Stop on store a000) 2/\(C:$e5cf) l "qft.8000-c010" 8 Loading qft.8000-c010 from 8000 to C00F (4010 bytes) (C:$e5cf) bk store a000 WATCH: 1 C:$a000 (Stop on store) (C:$e5cf) bank default (C:$e5cf) g fce2 #1 (Stop on store a000) 2/$002, 10/$0a .C:fd73 91 C1 STA ($C1),Y - A:55 X:94 Y:00 SP:fd ..-..I.C 2315364035 (C:$fd75) m c1 c2 >C:00c1 00 a0 ..2, 10/\(C:$e5cf) l "qft.8000-c010" 8 Loading qft.8000-c010 from 8000 to C00F (4010 bytes) (C:$e5cf) bk store a000 WATCH: 1 C:$a000 (Stop on store) (C:$e5cf) bank default (C:$e5cf) g fce2 #1 (Stop on store a000) 2/$002, 10/$0a .C:fd73 91 C1 STA ($C1),Y - A:55 X:94 Y:00 SP:fd ..-..I.C 2315364035 (C:$fd75) m c1 c2 >C:00c1 00 a0 ..a .C:fd73 91 C1 STA ($C1),Y - A:55 X:94 Y:00 SP:fd ..-..I.C 2315364035 (C:$fd75) m c1 c2 >C:00c1 00 a0 ..

And there’s our culprit. For some reason, the instruction at $FD73 is being executed, and that instruction stores the value of the A register ($55) into the location pointed to by $C1 and $C2, which is $A000 (remember, the CPU is little-endian). The value of the Y register is added to the destination address before the store happens, but Y is currently 0, so that doesn’t change anything. What is address $FD73, and why is it writing into our program’s code? Why is it even executing at all? The monitor’s backtrace command might help us find out.

(C:$00c3) bt (0) 800f (C:$00c3)

Interesting. The caller of this routine is at $800F, which is very near the start of our game’s machine code. Let’s disassemble the code from the beginning and look at $800F.

(C:$00c3) d 8000 8020 .C:8000 00 BRK .C:8001 C0 20 CPY #$20 .C:8003 80 C3 NOOP #$C3 .C:8005 C2 CD NOOP #$CD .C:8007 38 SEC .C:8008 30 8E BMI $7F98 .C:800a 16 D0 ASL $D0,X .C:800c 20 A3 FD JSR $FDA3 .C:800f 20 50 FD JSR $FD50 .C:8012 20 15 FD JSR $FD15 .C:8015 20 18 E5 JSR $E518 .C:8018 58 CLI .C:8019 78 SEI .C:801a 4C 47 FE JMP $FE47 .C:801d 8D 18 03 STA $0318 .C:8020 20 BC F6 JSR $F6BC (C:$8023)

RAMTAS

At $800F, we find the instruction JSR $FD50. This instruction calls the subroutine at the specified address. $FD50 is pretty close to the offending instruction, $FD73, so this makes sense. $FD50 is within the KERNAL ROM’s address space, and is in fact a documented routine, named RAMTAS, that can be called by other programs. The pagetable.com KERNAL API reference says this about RAMTAS:

Perform RAM test

- Communication registers: A, X, Y

- Preparatory routines: None

- Error returns: None

- Stack requirements: 2

- Registers affected: A, X, Y

Description: This routine is used to test RAM and set the top and bottom of memory pointers accordingly. It also clears locations $00 to $0101 and $0200 to $03FF. It also allocates the cassette buffer, and sets the screen base to $0400. Normally, this routine is called as part of the initialization process of a Commodore 64 program cartridge.

and also this:

RAMTAS

This routine clears zero-page RAM (locations $02-$FF) and initializes Kernal memory pointers in zero page. For the 64 only, the routine also clears pages 2 and 3 (locations $0200-$03FF), tests all RAM locations from $0400 upwards until ROM is encountered, and sets the top-of-memory pointer. For the 128, the routine sets the BASIC restart vector ($0A00) to point to BASIC’s cold-start entry address, $4000.

This line is particularly interesting: “Normally, this routine is called as part of the initialization process of a Commodore 64 program cartridge.” Quest for Tires was released both on floppy disk and on ROM cartridge, and there were some utility programs available to convert a cartridge program to be able to load and run from disk. Furthermore, ROM cartridges use the memory space $8000–$9FFF for 8k cartridges, and $8000–$BFFF for 16k cartridges. This latter range matches our code’s address range almost exactly. It seems probable that this floppy disk copy of the game was originally created by converting from the cartridge version. The extra 16 bytes at the end could be some glue code to help with the conversion.

Cartridge Conversion

Why does it matter that this code was converted from a cartridge? First, it explains why the BASIC loader resets the computer to start the game. Cartridges are inserted before powering on the computer, and when the booting system notices that a cartridge is plugged in, it starts executing code from that cartridge. Also, since the game was originally a cartridge, it needs to call the RAMTAS routine itself, as the KERNAL doesn’t do that automatically when a cartridge is inserted.

The RAMTAS routine, among other things, writes a $55 byte (sound familiar?) to each memory location and reads it back to make sure it matches. If the byte matches, the original byte that was stored at the location is restored, and testing moves on to the next address. If the byte doesn’t match, the routine assumes it’s found a ROM, stops testing RAM, and updates some KERNAL pointers to indicate where the top and bottom of RAM are. Take a look at the C64 BASIC & KERNAL ROM Disassembly section of Michael Steil’s reference site for full details on this routine.

When the game is run from a ROM cartridge, it’s mapped into memory at $8000–$BFFF. As part of its initialization, it calls RAMTAS, which then starts testing RAM, but stops at $8000, because it hits the ROM. But, when the game is in RAM instead, RAMTAS keeps going when it hits $8000. This is generally non-destructive, since each byte is put back after it passes the RAM test. However, recall that the BASIC ROM is mapped in at $A000–$BFFF, the first byte of which is exactly our problem address.

Here’s the crucial point. RAMTAS writes $55 to $A000, and reads back a different value (the first byte in the BASIC ROM), so it (correctly) concludes that it’s found a ROM. However, it has already written to the RAM underneath the ROM at that address, which is holding our program! Furthermore, RAMTAS doesn’t try to restore the byte, since it thinks it’s from a ROM, and what would be the point of trying to write to ROM? This is the root cause of our corrupted byte.

But shouldn’t the BASIC ROM be banked out already? It’s masking half of the game code, so it will need to be banked out for the game to be able to run. Let’s take a look at that glue code at $C000 to $C00F.

Glue Code

When the C64 boots up, it looks at addresses $8004 to $8008 for the byte sequence $C3 $C2 $CD $38 $30. That’s PETSCII for “CBM80”. “CBM” stands for Commodore Business Machines. I’m not sure what the “80” signifies. If that sequence is found, the system sets the NMI (Non-Maskable Interrupt) vector to point to the address found at $8002 and $8003. The C64’s Restore key is wired to the CPU’s NMI line, so pressing that key will trigger an NMI and jump to the address pointed to by the NMI vector. After setting up the vector, the system jumps to the address pointed to by $8000 and $8001 and starts executing code there.

If we look at memory at $8000 to $8008, we find the CBM80 signature at $8004, and the two pointers at $8000 and $8002:

(C:$8023) m 8004 8008 >C:8004 c3 c2 cd 38 30 ...80 (C:$8009) m 8000 8001 >C:8000 00 c0 .. (C:$8002) m 8002 8003 >C:8002 20 80 .

This is definitely a cartridge conversion, or at the very least, is using the cartridge mechanism. $8000 points to $C000, so that’s where the system will start executing code once it’s finished booting. Notably, this is just outside the 16k ROM cartridge address range, so it must have been added by the conversion utility. Let’s look at that code:

(C:$8004) d c000 c00f .C:c000 A9 36 LDA #$36 .C:c002 85 01 STA $01 .C:c004 4C 09 80 JMP $8009 .C:c007 AA TAX .C:c008 AA TAX .C:c009 AA TAX .C:c00a AA TAX .C:c00b AA TAX .C:c00c AA TAX .C:c00d AA TAX .C:c00e AA TAX .C:c00f AA TAX

Aha, the first two instructions set the memory bank register to $36, or %00110110 in binary. The default value for this register is $37, or %00110111 in binary, so this clears the lowest-order bit. That happens to be the bit that controls the BASIC ROM, and setting it to 0 banks out that ROM. This is the sort of thing we should expect to see here.

The next instruction jumps to the start of the game code. It’s likely that the original cartridge had the entry point at $8000 set to $8009, and the conversion utility redirected execution to $C000, where it put code to bank out the BASIC ROM (because that’s necessary when running from RAM) and then jump back to where the code would have started. The remaining $AA bytes are simply padding to ensure that the file size is a multiple of 16 bytes. That’s not really necessary, but it doesn’t hurt anything either.

This technique is sometimes referred to as patching, although that term is more broadly applicable than this specific approach. The additional code itself is sometimes called patch code, for hopefully obvious reasons, or glue code, since its purpose is to stick together things that normally don’t go together (in this case, code from a ROM cartridge running from RAM).

If the glue code sets the bank register to bank out the BASIC ROM, why is the RAMTAS routine hitting it and messing up the game code? Let’s trace through the glue code and see if we can find out.

(C:$c010) l "qft.8000-c010" 8 Loading qft.8000-c010 from 8000 to C00F (4010 bytes) (C:$c010) bk c000 BREAK: 1 C:$c000 (Stop on exec) (C:$c010) g fce2 #1 (Stop on exec c000) 60/\c, 17/\ .C:c000 A9 36 LDA #$36 - A:C3 X:00 Y:91 SP:ff ..-..IZC 6482922 (C:$c000) m 00 01 >C:0000 2f 37 /7 (C:$0002) z .C:c002 85 01 STA $01 - A:36 X:00 Y:91 SP:ff ..-..I.C 6482924 (C:$c002) z .C:c004 4C 09 80 JMP $8009 - A:36 X:00 Y:91 SP:ff ..-..I.C 6482927 (C:$c004) m 00 01 >C:0000 2f 36 /6 (C:$0002) z .C:8009 8E 16 D0 STX $D016 - A:36 X:00 Y:91 SP:ff ..-..I.C 6482930 (C:$8009) z .C:800c 20 A3 FD JSR $FDA3 - A:36 X:00 Y:91 SP:ff ..-..I.C 6482934 (C:$800c) m 00 01 >C:0000 2f 36 /6 (C:$0002) n .C:800f 20 50 FD JSR $FD50 - A:D7 X:FF Y:91 SP:ff N.-..I.C 6483073 (C:$800f) m 00 01 >C:0000 2f 37 /7

As we can see from this trace, The glue code does, in fact, successfully bank out the BASIC ROM, and it stays banked out right up until the JSR $FDA3 subroutine call at $800C. That routine must have banked it back in, just before the call to RAMTAS ($FD50). What is this routine?

IOINIT

According to pagetable.com’s KERNAL ROM disassembly and KERNAL API reference, $FDA3 contains a KERNAL routine named IOINIT. This is what it has to say about that routine:

Initialize I/O devices

- Communication registers: None

- Preparatory routines: None

- Error returns:

- Stack requirements: None

- Registers affected: A, X, Y

Description: This routine initializes all input/output devices and routines. It is normally called as part of the initialization procedure of a Commodore 64 program cartridge.

EXAMPLE:

JSR IOINIT

and also this:

Initialize I/O devices

Called by: None.

JMP FDA3 to initialize the CIA registers, the 6510 I/O data registers, the SID chip registers, start CIA #1 timer A, enable CIA #1 timer A interrupts, and set the serial clock output line high.

The closest equivalent to this routine on the VIC is JMP FDF9 to initialize the 6522 registers, set VIA #2 timer 1 value, start timer 1, and enable timer 1 interrupts.

Since these routines are called during system reset, the main use for IOINIT is for an autostart cartridge that wants to use the same I/O settings that the Kernal normally uses.

So, ultimately, the cartridge conversion utility used a patch and some glue code to bank out the BASIC ROM to let the game run, but wasn’t clever enough to notice that IOINIT banks it back in right away, and then RAMTAS comes along and clobbers the code at $A000, leading to the crash bug we’ve been diagnosing. This is almost everything we need to know to understand why the game crashes when it does, but one small question remains. If the BASIC ROM has been banked in over the top of the second half of the game code, how does the game run at all?

The answer is that, a few instructions later, the game code itself banks the BASIC ROM back out again, and so it’s only banked in for a brief moment, during which RAMTAS gets confused and introduces the bug.

(C:$0002) d 8009 8033 .C:8009 8E 16 D0 STX $D016 .C:800c 20 A3 FD JSR $FDA3 .C:800f 20 50 FD JSR $FD50 .C:8012 20 15 FD JSR $FD15 .C:8015 20 18 E5 JSR $E518 .C:8018 58 CLI .C:8019 78 SEI .C:801a 4C 47 FE JMP $FE47 .C:801d 8D 18 03 STA $0318 .C:8020 20 BC F6 JSR $F6BC .C:8023 20 15 FD JSR $FD15 .C:8026 20 A3 FD JSR $FDA3 .C:8029 20 18 E5 JSR $E518 .C:802c 58 CLI .C:802d A9 36 LDA #$36 .C:802f 85 01 STA $01 .C:8031 4C CD 8F JMP $8FCD

At $802D–$8030, the game sets $01 back to $36, banking out the BASIC ROM (for good this time) and then jumps off to $8FCD, which presumably shows the title screen and then starts the game itself.

Fixing the Bug

Now that we’ve figured out what’s going wrong, how do we fix it? Through my journey diagnosing this issue, I’ve tried several different approaches, some of which were successful. In this section, I’ll describe some of the successful fixes and discuss their pros and cons.

Fix 1: Avoid the Corrupted Instruction

The first fix I tried that actually worked was to adjust to code to skip over the instruction at $A000, instead achieving the same effect by jumping somewhere else. Recall that the correct instruction is INC $4024, which is followed by LDA $4024 at location $A003. Let’s see if we can find another place in the code that does that:

(C:$8034) h 8000 bfff ee 24 40 9fe8 a000

There are only two instances of that instruction in the entire program. One of them is $A000, which is what we’re trying to avoid. Let’s look at the other one at $9FE8:

(C:$8034) d 9fe8 9ffd .C:9fe8 EE 24 40 INC $4024 .C:9feb 4C 03 A0 JMP $A003 .C:9fee EE 61 40 INC $4061 .C:9ff1 CE 24 40 DEC $4024 .C:9ff4 AD 24 40 LDA $4024 .C:9ff7 C9 04 CMP #$04 .C:9ff9 B0 08 BCS $A003 .C:9ffb 4C 00 A0 JMP $A000

As expected, the code at $9FE8 executes the same increment instruction as the one that got corrupted. However, somewhat miraculously, it then unconditionally jumps to $A003, which is immediately after the corrupted instruction, and just where we need to go next. So, if we replace every jump to $A000 with a jump to $9FE8 instead, that should avoid the corruption and do what the original program intended. Let’s look for the places we need to change:

(C:$9ffe) h 8000 bfff 4c 00 a0 9ffb bffb

Only two places found. The first ($9FFB), we just saw above. What about the second?

(C:$9ffe) d bfe0 bfff .C:bfe0 01 80 ORA ($80,X) .C:bfe2 01 80 ORA ($80,X) .C:bfe4 01 80 ORA ($80,X) .C:bfe6 01 80 ORA ($80,X) .C:bfe8 01 1E ORA ($1E,X) .C:bfea 1F 20 46 SLO $4620,X .C:bfed 47 48 SRE $48 .C:bfef 6E 6F 70 ROR $706F .C:bff2 97 98 SAX $98,Y .C:bff4 BF C0 E6 LAX $E6C0,Y .C:bff7 E7 E8 ISB $E8 .C:bff9 B0 08 BCS $C003 .C:bffb 4C 00 A0 JMP $A000 .C:bffe F9 07 A9 SBC $A907,Y

This is basically gibberish, so it’s probably not code. It’s likely some sort of data, perhaps graphics or sound data. We shouldn’t need to worry about this, so the only JMP $A000 instruction we’ve found that we need to update is the one at $9FFB. Note that there could be conditional branch instructions or indirect jump instructions that target $A000.

The branch instructions would be within the 256 bytes around $A000, since they can only jump a limited distance. That’s still lot of disassembly code to show, however, so perhaps you’ll take my word for it that I looked and didn’t see any. Indirect jumps to a specific location are hard to find, since it would require dynamic analysis of the code to determine the jump target. If we miss one, the game might still crash, but let’s try it and see what happens. The following commands make the change and then save the updated code to a new file on disk called "FIX1.8000-C010".

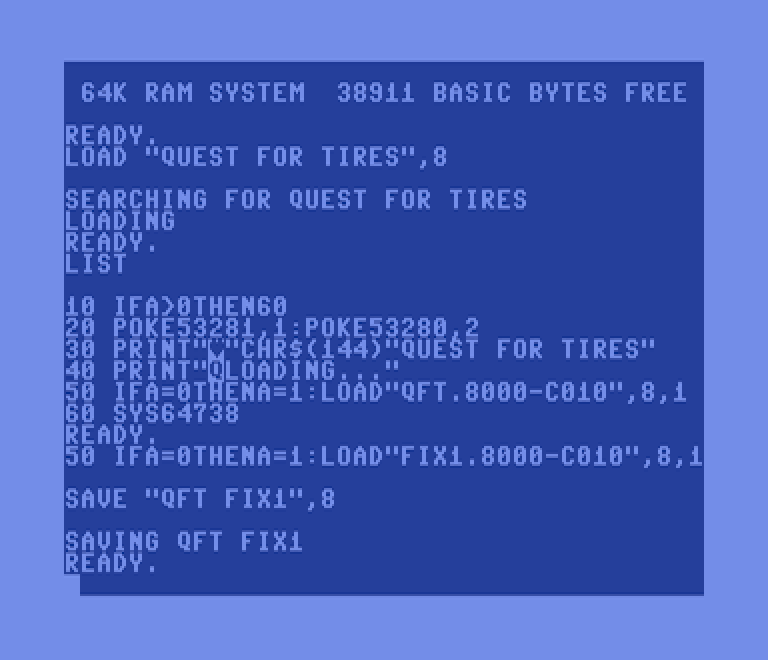

(C:$c000) a 9ffb .9ffb jmp $9fe8 .9ffe (C:$9ffe) d 9fe8 9ffd .C:9fe8 EE 24 40 INC $4024 .C:9feb 4C 03 A0 JMP $A003 .C:9fee EE 61 40 INC $4061 .C:9ff1 CE 24 40 DEC $4024 .C:9ff4 AD 24 40 LDA $4024 .C:9ff7 C9 04 CMP #$04 .C:9ff9 B0 08 BCS $A003 .C:9ffb 4C E8 9F JMP $9FE8 (C:$9ffe) bank ram (C:$9ffe) s "fix1.8000-c010" 8 8000 c00f Saving file `fix1.8000-c010' from $8000 to $c00f

Next, we need to update the BASIC loader to load our fixed version of the code:

Now, all that’s left to do is try it! I started this section by saying I would only discuss successful fixes, so there’s not much suspense, but here’s a video of this fixed code running, with the speed going all the way up to 80 without crashing! 😀

Clearly, this fix works, which is great. One downside, however, is that it slightly changes the number of cycles it takes to execute the speed update code during the main game loop. In practice, it’s unlikely to matter, but it might subtly change the gameplay. Another drawback is more aesthetic—it’s not the same control flow as what was originally published. Let’s see how we might improve on this.

Fix 2: Undo the Corruption

Instead of modifying the main game loop, maybe there’s a way we can repair the damage RAMTAS did to our code. We know exactly which byte it clobbered and what the value was before said clobbering. Perhaps we can borrow the trick that the cartridge conversion utility used, and insert some code right after RAMTAS returns that restores the byte’s original value. We have nine padding bytes to work with, and since this is stored on a disk, we could add quite a bit of extra code if we needed to. But, I think we can fit what we need to do into the existing padding bytes.

What we want to do is store the value $EE into the location $A000 as soon as possible after the call to RAMTAS returns. One way to do that is to write our own subroutine that calls RAMTAS and then immediately fixes up memory before returning. That would look something like this:

(C:$9ffe) l "qft.8000-c010" 8 Loading qft.8000-c010 from 8000 to C00F (4010 bytes) (C:$9ffe) d c000 c00f .C:c000 A9 36 LDA #$36 .C:c002 85 01 STA $01 .C:c004 4C 09 80 JMP $8009 .C:c007 AA TAX .C:c008 AA TAX .C:c009 AA TAX .C:c00a AA TAX .C:c00b AA TAX .C:c00c AA TAX .C:c00d AA TAX .C:c00e AA TAX .C:c00f AA TAX (C:$c010) a c007 .c007 jsr $fd50 .c00a lda #$ee .c00c sta $a000 .c00f rts .c010 (C:$c010) d c000 c00f .C:c000 A9 36 LDA #$36 .C:c002 85 01 STA $01 .C:c004 4C 09 80 JMP $8009 .C:c007 20 50 FD JSR $FD50 .C:c00a A9 EE LDA #$EE .C:c00c 8D 00 A0 STA $A000 .C:c00f 60 RTS

We used up all the padding bytes, but we now have the routine we need stored in memory. Next, we need to patch the game code to call our routine instead of calling RAMTAS directly:

(C:$c010) d 8009 8018 .C:8009 8E 16 D0 STX $D016 .C:800c 20 A3 FD JSR $FDA3 .C:800f 20 50 FD JSR $FD50 .C:8012 20 15 FD JSR $FD15 .C:8015 20 18 E5 JSR $E518 .C:8018 58 CLI (C:$8019) a 800f .800f jsr $c007 .8012 (C:$8012) d 8009 8018 .C:8009 8E 16 D0 STX $D016 .C:800c 20 A3 FD JSR $FDA3 .C:800f 20 07 C0 JSR $C007 .C:8012 20 15 FD JSR $FD15 .C:8015 20 18 E5 JSR $E518 .C:8018 58 CLI

And that should do it. Let’s save the code, set some breakpoints, start the game, and trace through to make sure our patch restores the value of $A000 to $EE and then resumes normal execution, as we expect:

(C:$8019) bank ram (C:$8019) s "fix2.8000-c010" 8 8000 c00f Saving file `fix2.8000-c010' from $8000 to $c00f (C:$8019) bk 800f BREAK: 1 C:$800f (Stop on exec) (C:$8019) bk c00a BREAK: 2 C:$c00a (Stop on exec) (C:$8019) g fce2 #1 (Stop on exec 800f) 77/\d, 49/\ .C:800f 20 07 C0 JSR $C007 - A:D7 X:FF Y:A0 SP:ff N.-..I.C 49939549 (C:$800f) m a000 a000 >C:a000 ee . (C:$a001) z .C:c007 20 50 FD JSR $FD50 - A:D7 X:FF Y:A0 SP:fd N.-..I.C 49939555 (C:$c007) n #2 (Stop on exec c00a) 156/\c, 62/\e .C:c00a A9 EE LDA #$EE - A:04 X:00 Y:A0 SP:fd ..-..I.. 52115762 (C:$c00a) m a000 a000 >C:a000 55 U (C:$a001) z .C:c00c 8D 00 A0 STA $A000 - A:EE X:00 Y:A0 SP:fd N.-..I.. 52115764 (C:$c00c) z .C:c00f 60 RTS - A:EE X:00 Y:A0 SP:fd N.-..I.. 52115768 (C:$c00f) m a000 a000 >C:a000 ee . (C:$a001) z .C:8012 20 15 FD JSR $FD15 - A:EE X:00 Y:A0 SP:ff N.-..I.. 52115774

It worked! The trace shows that execution gets diverted to our new routine. Before we call RAMTAS, $A000 has the correct value. After RAMTAS returns, the value is corrupted. But after the next two instructions, it’s restored to the correct value again. Finally, our routine returns, and the game continues as if nothing happened.

This is much nicer than the first fix, because it doesn’t modify code in the middle of the game loop. It’s still annoying, however, that we have to let the code get corrupted in the first place. Perhaps we can improve this further.

Fix 3: Prevent the Corruption

Recall that the reason RAMTAS corrupts our program is that, even though the glue code banked out the BASIC ROM, the call to IOINIT banked it back in right before RAMTAS is called. What if we inserted some code between those two calls to bank it out again. Then RAMTAS should be able to complete without screwing anything up. Let’s give it a shot. First we set up our routine in the padding area, as before. This time, however, instead of calling RAMTAS right away, we set the bank register first. Then we jump directly to the RAMTAS routine, so that when it returns, it will return to our routine’s caller.

(C:$8012) l "qft.8000-c010" 8 Loading qft.8000-c010 from 8000 to C00F (4010 bytes) (C:$8012) d c000 c00f .C:c000 A9 36 LDA #$36 .C:c002 85 01 STA $01 .C:c004 4C 09 80 JMP $8009 .C:c007 AA TAX .C:c008 AA TAX .C:c009 AA TAX .C:c00a AA TAX .C:c00b AA TAX .C:c00c AA TAX .C:c00d AA TAX .C:c00e AA TAX .C:c00f AA TAX (C:$c010) a c007 .c007 lda #$36 .c009 sta $01 .c00b jmp fd50 .c00e (C:$c00e) d c000 c00f .C:c000 A9 36 LDA #$36 .C:c002 85 01 STA $01 .C:c004 4C 09 80 JMP $8009 .C:c007 A9 36 LDA #$36 .C:c009 85 01 STA $01 .C:c00b 4C 50 FD JMP $FD50 .C:c00e AA TAX .C:c00f AA TAX

Then, as before, we replace the original call to RAMTAS with a call to our routine instead:

(C:$c010) d 8009 8018 .C:8009 8E 16 D0 STX $D016 .C:800c 20 A3 FD JSR $FDA3 .C:800f 20 50 FD JSR $FD50 .C:8012 20 15 FD JSR $FD15 .C:8015 20 18 E5 JSR $E518 .C:8018 58 CLI (C:$8019) a 800f .800f jsr $c007 .8012 (C:$8012) d 8009 8018 .C:8009 8E 16 D0 STX $D016 .C:800c 20 A3 FD JSR $FDA3 .C:800f 20 07 C0 JSR $C007 .C:8012 20 15 FD JSR $FD15 .C:8015 20 18 E5 JSR $E518 .C:8018 58 CLI

All right, let’s try this out.

(C:$8019) bank ram (C:$8019) s "fix3.8000-c010" 8 8000 c00f Saving file `fix3.8000-c010' from $8000 to $c00f (C:$8019) bk 800f BREAK: 1 C:$800f (Stop on exec) (C:$8019) bk 8012 BREAK: 2 C:$8012 (Stop on exec) (C:$8019) g fce2 #1 (Stop on exec 800f) 184/\(C:$8019) bank ram (C:$8019) s "fix3.8000-c010" 8 8000 c00f Saving file `fix3.8000-c010' from $8000 to $c00f (C:$8019) bk 800f BREAK: 1 C:$800f (Stop on exec) (C:$8019) bk 8012 BREAK: 2 C:$8012 (Stop on exec) (C:$8019) g fce2 #1 (Stop on exec 800f) 184/$0b8, 60/$3c .C:800f 20 07 C0 JSR $C007 - A:D7 X:FF Y:0A SP:ff N.-..I.C 4200295 (C:$800f) bank default (C:$800f) m 00 01 >C:0000 2f 37 /7 (C:$0002) bank ram (C:$0002) m a000 a000 >C:a000 ee . (C:$a001) z .C:c007 A9 36 LDA #$36 - A:D7 X:FF Y:0A SP:fd N.-..I.C 4200301 (C:$c007) z .C:c009 85 01 STA $01 - A:36 X:FF Y:0A SP:fd ..-..I.C 4200303 (C:$c009) z .C:c00b 4C 50 FD JMP $FD50 - A:36 X:FF Y:0A SP:fd ..-..I.C 4200306 (C:$c00b) bank default (C:$c00b) m 00 01 >C:0000 2f 36 /6 (C:$0002) g #2 (Stop on exec 8012) 39/$027, 2/$02 .C:8012 20 15 FD JSR $FD15 - A:04 X:11 Y:D0 SP:ff ..-..I.. 6994392 (C:$8012) bank default (C:$8012) m 00 01 >C:0000 2f 36 /6 (C:$0002) bank ram (C:$0002) m a000 a000 >C:a000 ee .b8, 60/\c .C:800f 20 07 C0 JSR $C007 - A:D7 X:FF Y:0A SP:ff N.-..I.C 4200295 (C:$800f) bank default (C:$800f) m 00 01 >C:0000 2f 37 /7 (C:$0002) bank ram (C:$0002) m a000 a000 >C:a000 ee . (C:$a001) z .C:c007 A9 36 LDA #$36 - A:D7 X:FF Y:0A SP:fd N.-..I.C 4200301 (C:$c007) z .C:c009 85 01 STA $01 - A:36 X:FF Y:0A SP:fd ..-..I.C 4200303 (C:$c009) z .C:c00b 4C 50 FD JMP $FD50 - A:36 X:FF Y:0A SP:fd ..-..I.C 4200306 (C:$c00b) bank default (C:$c00b) m 00 01 >C:0000 2f 36 /6 (C:$0002) g #2 (Stop on exec 8012) 39/\7, 2/\ .C:8012 20 15 FD JSR $FD15 - A:04 X:11 Y:D0 SP:ff ..-..I.. 6994392 (C:$8012) bank default (C:$8012) m 00 01 >C:0000 2f 36 /6 (C:$0002) bank ram (C:$0002) m a000 a000 >C:a000 ee .

This worked nicely. Because we set the bank register before calling RAMTAS, $A000 was never corrupted. As before, the game continues after our patch, none the wiser. This is a pretty good fix, but there’s one thing I can think of that might be even better.

Fix 4: Prevent the Corruption, but Even Better

The reason the game code calls IOINIT and RAMTAS is that, as a ROM cartridge, these routines would not be called by the KERNAL during bootup. However, we’re not running this code from ROM anymore, and there’s no cartridge in the expansion port. Maybe these calls are redundant, and could be entirely eliminated. Let’s remove the calls, and set some breakpoints to see if the routines still get called from somewhere else.

To remove these subroutine calls, the simplest thing to do is overwrite them with the NOP instruction. That’s a one-byte instruction that tells the processor to do nothing for a couple of clock cycles. Each subroutine call assembles to three bytes of code, so we need to put in six NOPs in total, starting at $800C.

(C:$e5cd) l "qft.8000-c010" 8 Loading qft.8000-c010 from 8000 to C00F (4010 bytes) (C:$e5cd) d 8009 8018 .C:8009 8E 16 D0 STX $D016 .C:800c 20 A3 FD JSR $FDA3 .C:800f 20 50 FD JSR $FD50 .C:8012 20 15 FD JSR $FD15 .C:8015 20 18 E5 JSR $E518 .C:8018 58 CLI (C:$8019) a 800c .800c nop .800d nop .800e nop .800f nop .8010 nop .8011 nop .8012 (C:$8012) d 8009 8018 .C:8009 8E 16 D0 STX $D016 .C:800c EA NOP .C:800d EA NOP .C:800e EA NOP .C:800f EA NOP .C:8010 EA NOP .C:8011 EA NOP .C:8012 20 15 FD JSR $FD15 .C:8015 20 18 E5 JSR $E518 .C:8018 58 CLI

Okay, let’s try it:

(C:$8019) bank ram (C:$8019) s "fix4.8000-c010" 8 8000 c00f Saving file `fix4.8000-c010' from $8000 to $c00f (C:$8019) bk fda3 BREAK: 1 C:$fda3 (Stop on exec) (C:$8019) bk fd50 BREAK: 2 C:$fd50 (Stop on exec) (C:$8019) g fce2 #1 (Stop on exec fda3) 66/\2, 2/\ .C:fda3 A9 7F LDA #$7F - A:31 X:30 Y:FF SP:fa N.-..I.. 34382337 (C:$fda3) g

The breakpoint at IOINIT was hit, so the KERNAL must be calling that for us. The breakpoint at RAMTAS wasn’t hit. Interestingly, however, the game still started and ran just fine, and did not exhibit the crash bug. Apparently neither of these calls was needed. So, we have a fix that consists solely of removing two subroutine calls in the initialization code for the game, and replacing them with NOPs. That feels pretty elegant to me, and so I’m going to call this solved. There may be even more elegant solutions, and I’d love to hear about them, but I’m pretty happy with this.

Conclusion

When I started the process of diagnosing and fixing this crash, I had no idea what I’d find, or whether it would be something I could fix. It was a lot of fun though. There were quite a few twists and turns, and I’ve now fixed the copy of a game I’ve had since childhood, which is pretty cool.

Out of curiosity, I tried a few different copies of Quest for Tires that I acquired from places (ahem), both disk and cartridge images, and none of them exhibited this bug. So, it seems that it was a quirk of my particular copy. (I’m honestly not even sure exactly where the disk came from.) I suppose I could just play those copies, but it feels very satisfying to be able to play the version I grew up with, albeit slightly altered, without any more crashing.

This is the first time I’ve dug into the code of a commercial C64 game to try to make modifications, and I might not have been as efficient as someone more experienced in this domain. If I’ve made mistakes, or made inaccurate statements, or done things the hard way, I’d love to hear about it. I’d also very much like to hear about other solutions people might come up with to fix the crash. In any case, I hope you found this at least a bit entertaining, and possibly even educational. I definitely learned a lot.

Leave a Reply