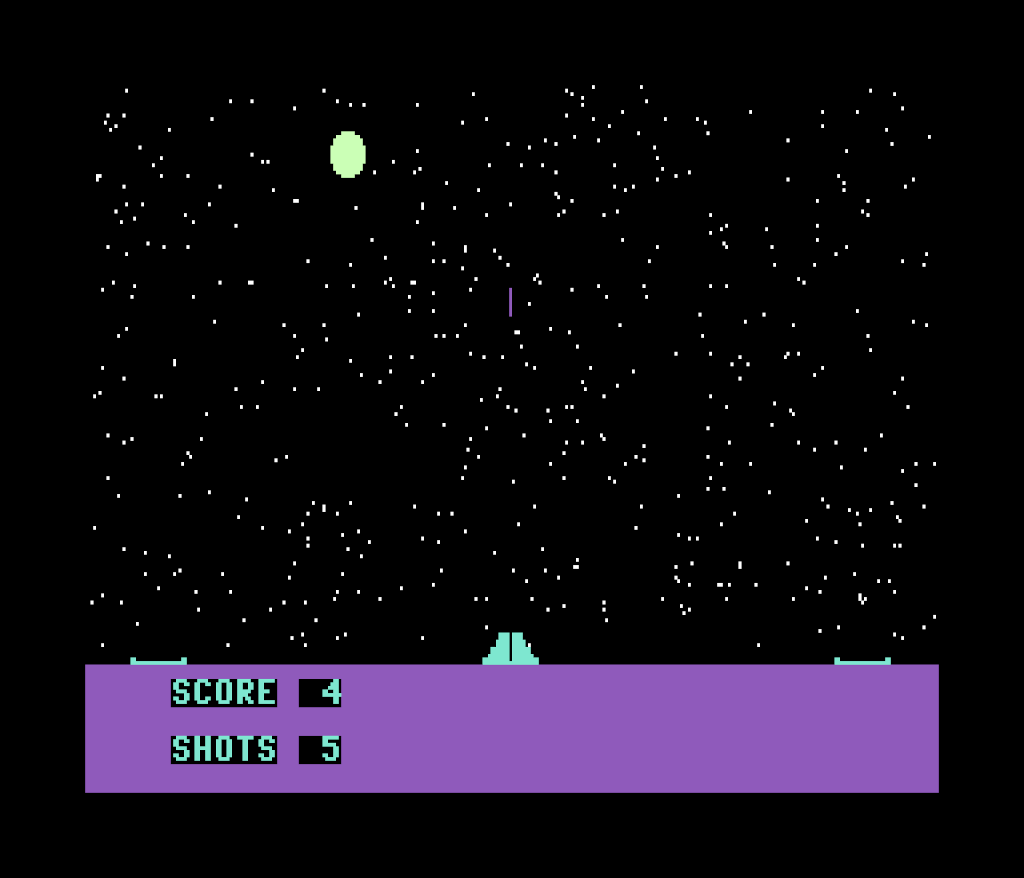

When I was about 11 or 12 years old, I wrote a simple game in Commodore 128 BASIC. It’s not very fancy, but it is a complete game, with sound, graphics, a title screen, and even a backstory. The object of the game is to fire missiles at a moon moving across the top of the screen. The player can move the missile launcher to one of three bases using the joystick, and (of course) launch missiles with the fire button. By any standard, it’s not a great game, but I was pretty proud of it at the time.

The C128 included Commodore BASIC 7.0, which was much better than the older Commodore BASIC 2.0 that was on the C64. BASIC 7.0 had lots of additional commands to control the graphics and sound chips in the machine, read the joysticks, save and load binary files between RAM and disk, etc., and the computer came with a really nice system guide [PDF] that described all of them. 6502 machine language was out of my reach at the time—I didn’t have an assembler, or even any reference material. The C128 included a machine language monitor with a rudimentary assembler, but I had no idea what it was for. Nevertheless, I decided to try to make a game using the enhanced C128 BASIC, and Moon Blaster was the result.

Machine Language Port

My recent foray into C64 game reverse-engineering gave me an idea: re-write Moon Blaster in assembly language for the C64. I’ve never written a game in machine language for the C64 before, and this game is pretty simple—great for a first project. I had a couple main goals: 1) stay as true as possible to the original game, and 2) build both disk and cartridge versions. I’m pleased to report that I was successful. Here’s a short video of the new version of the game (headphone warning, it might be a bit loud):

If you’d like to play the game, you can download it here. The download contains cartridge and disk images for the new version, as well as the assembly source code for it. It also includes a disk image of the original BASIC game, if you’d like to compare the two. You’ll need a C64/C128 emulator (VICE is a good one), or a real C64/C128. (If you’re using real hardware, I’ll assume you know how to get the images to it. If not, let me know.) The easiest way to start the game in VICE is to attach the cartridge image, either by using the menu or by pressing Alt+C. You’ll need to set up the joystick as well. VICE works with a game controller, or can emulate a joystick using the keyboard. It’s pretty straightforward to set up, but if you have trouble, let me know.

It’s Not a Bug

An amusing story (at least to me) about Moon Blaster is the way I inadvertently introduced the concept of a critical hit. The moving objects on the screen—the moon, missile launcher, and missiles—were implemented as sprites. C128 BASIC included commands for sprite collision detection, which I used to detect when the player got a hit. When two sprites touch, the program jumps to a specified line, which in this case plays the hit sound, updates the score, etc.

Unfortunately, BASIC is so slow that, in the original game, if the player hit the moon close to dead center, the missile collided twice before it was moved back to the launcher. This had the effect of doubling the hit sound and animation, and scoring twice instead of once. I recall trying to fix it, and being stumped. Ultimately, in the grand tradition of “It’s not a bug; it’s a feature,” I decided just to add it to the instructions as an “intentional” bonus. However, the machine language version runs much faster, so this didn’t happen, and to stay true to the original, I actually had to write code specifically to replicate this bug feature.

Technical Stuff

The rest of this post contains technical details intended to be of interest to other programmers. If you’re not a programmer, you’re welcome to stick around, but if you want to bail at this point, I won’t mind 😀. I won’t go over all of the game code, but there were a few things I was pretty happy with, and I thought they were worth talking about. The assembler I used for this project is ca65, which is part of the cc65 compiler suite. In case it’s helpful, here’s a link to a 6502 instruction set reference.

Linear Feedback Shift Register

The original game initially used BASIC drawing commands to draw the star field. This was painfully slow, so I ended up changing it to load the bitmap memory from a disk file, which I had saved after running the drawing routines. This was still pretty slow, but was a noticeable improvement. When doing the assembly port, I had the raw power of a 1 MHz processor at my command, so I decided the game should draw the stars at startup every time. Doing this in machine code is way faster than loading a screen image from disk. Plus, with the cartridge version, there wouldn’t even be a disk.

However, I wanted the stars to be the same every time, too, so I needed a pseudorandom number generator. The SID sound chip in the C64 can be used to generate random numbers, but there’s not a good way to seed it. So using that approach, the stars would change every game. Instead, I implemented a 16-bit Linear Feedback Shift Register (LFSR) routine, and sampled bits from it to get pseudorandom coordinates for drawing the stars. I used the constants from the Wikipedia article, since that seemed as good a set as any. I don’t claim it’s the most optimal LFSR ever written for the 6502, but I think it’s pretty slick:

.EXPORTZP LFSR_STATE = $fd

.CODE

.PROC lfsr_16

; get XOR of bits 15 and 13

lda LFSR_STATE+1

lsr a

lsr a

eor LFSR_STATE+1

; get XOR of bit 12

lsr a

eor LFSR_STATE+1

; get XOR of bit 10

lsr a

lsr a

eor LFSR_STATE+1

; put result of XORs into carry flag

lsr a

lsr a

lsr a

; rotate carry flag into LFSR_STATE as the LSB

rol LFSR_STATE

rol LFSR_STATE+1

rts

.ENDPROC ; lfsr_16

Raster Interrupt Split-Screen

The game is mostly graphical, but there are text elements to display the score and number of shots fired. C128 BASIC has a command (CHAR) to draw character on a bitmap screen. I could have taken the same approach with the machine language port, but that would involve banking in the character ROM and copying the bitmap data for each character. It would be slow (although I had plenty of cycles to do it since the game is so simple) and ugly code. Instead, I decided to go a different direction—changing between graphics and text mode in the middle of the frame.

The VIC-II video chip in the C64 can be configured to cause an interrupt when it reaches a specified scan line—a so-called raster interrupt. To achieve a split screen effect, one can enable the raster interrupt at the top of the screen, and then in the interrupt handler, turn on graphics mode, then set the raster interrupt somewhere in the middle of the screen, and turn on text mode. There are a few other details to take care of, but this works surprisingly well. To print the score, I can simply place the characters in the right location in screen memory. Here’s the code I used to enable the interrupt, and the interrupt handler that implements the split-screen:

.INCLUDE "vic2.inc"

IRQ_VECTOR = $0314

KERNAL_ISR = $ea31

CIA1_IRQ = $dc0d

CIA2_IRQ = $dd0d

.DATA

FRAME_SYNC: .res 1

.CODE

.PROC setup_irq

sei

; disable CIA-1 interrupts

lda #%01111111

sta CIA1_IRQ

; clear high bit of raster counter

and VIC2::CR1

sta VIC2::CR1

; acknowledge pending interrupts

lda CIA1_IRQ

lda CIA2_IRQ

; set raster interrupt

lda #0 ; interrupt on this raster line

sta VIC2::RST

; clear frame sync variable

sta FRAME_SYNC

; set interrupt vector

lda #<split_screen_isr

sta IRQ_VECTOR

lda #>split_screen_isr

sta IRQ_VECTOR+1

; enable raster interrupts

lda #%00000001

sta VIC2::IMA

cli

rts

.ENDPROC ; setup_irq

.PROC teardown_irq

sei

; disable raster interrupts

lda #%00000000

sta VIC2::IMA

; acknowledge pending interrupts

asl VIC2::IRQ ; acknowledge VIC-II raster interrupt by clearing low bit

; enable CIA-1 interrupts

lda #%11111111

sta CIA1_IRQ

; restore interrupt vector

lda #<KERNAL_ISR

sta IRQ_VECTOR

lda #>KERNAL_ISR

sta IRQ_VECTOR+1

cli

rts

.ENDPROC ; teardown_irq

.PROC split_screen_isr

; clear decimal flag

cld

; look at current raster line to see if we should turn bitmap on or off

lda VIC2::CR1

ldx VIC2::RST

cpx #100

bcs bitmap_off

; turn bitmap mode on

bitmap_on:

inc FRAME_SYNC

ora #%00100000 ; bitmap on

sta VIC2::CR1

lda VIC2::PTR

ora #%00001100 ; set bitmap memory to $2000-$3FFF

and #%11111100

sta VIC2::PTR

lda #209 ; next interrupt raster line

jmp return

; turn bitmap mode off

bitmap_off:

and #%11011111 ; bitmap off

sta VIC2::CR1

lda VIC2::PTR

ora #%00000100 ; set bitmap memory to $0000-$1FFF

and #%11110100

sta VIC2::PTR

lda #0 ; next interrupt raster line

return:

sta VIC2::RST

asl VIC2::IRQ ; acknowledge VIC-II raster interrupt by clearing low bit

jmp KERNAL_ISR

.ENDPROC ; split_screen_isr

Exit to BASIC

C64 games rarely include an option to exit the game and return to BASIC. Even though 64K of RAM was pretty roomy for the time, most games needed a great deal of it, and so banked out the BASIC ROM and clobbered BASIC memory areas. It’s also possible this was used as a rudimentary form of copy protection. However, the original Moon Blaster included an option to quit; being a BASIC program itself, this was simple to do.

I wanted the machine language port to have this same capability. It was in the original game, and I’m not worried about copy protection. The game doesn’t take much memory (less than 5K of code and data, not counting the 8K bitmap and 1K text screen memory areas), and I was able to place everything so as not to interfere with BASIC. To exit to BASIC, the disk-based game can simply jump to the BASIC warm-start routine $E38B. However, there are two problems with this.

The first problem is that just jumping to BASIC warm-start doesn’t work at all if you’re running the cartridge version, because BASIC isn’t initialized in that case. To address this, I call a few BASIC ROM routines from the cartridge entry point to initialize BASIC to the point that it can be warm-started. Here’s the code I used to do that:

.INCLUDE "main.inc"

.SEGMENT "START"

; entry point which jumps away to BASIC, so it works right from a cartidge

.PROC start

; initialize the KERNAL

jsr $fda3 ; initialize I/O devices

jsr $fd50 ; test RAM and initialize memory pointers

jsr $fd15 ; initialize KERNAL vectors

jsr $e518 ; initialize the screen and keyboard

cli ; enable interrupts

; initialize BASIC

jsr $e453 ; initialize BASIC vectors

jsr $e3bf ; initialize BASIC RAM

; run the game

jsr main

; jump to BASIC

ldx #$80 ; no error code

jmp $e38b ; BASIC warm start

.ENDPROC ; start

The second problem is that I wanted the user to be able to re-start the game simply by typing RUN. This kind of works with the disk version, but that runs the BASIC loader program and loads the whole game from disk again, even though it’s still in memory. With a cartridge, there would be no BASIC program to RUN at all. To deal with this, I included a simple BASIC program to restart the game in the constant data section. Before exiting, I replace whatever BASIC program is loaded (possibly none) with this program, which immediately starts the game again when run. To do this, not only the BASIC program area at $0801 needs to be populated, but also several pointers that BASIC uses, starting at $2B in zero page. (The details about these locations can be found in a C64 memory map.) Here’s the code I used to do that:

.RODATA

; BASIC program to re-start the game

;

; 10 SYS 32804

;

BASIC_LOADER_ADDR = $0801

BASIC_LOADER:

.byte $0d, $08, $0a, $00, $9e, $20, $33, $32, $38, $30, $34, $00, $00, $00

BASIC_LOADER_SIZE = * - BASIC_LOADER

BASIC_POINTERS_ADDR = $2b

BASIC_POINTERS:

.byte $01, $08, $0f, $08, $0f, $08, $0f, $08, $00, $80, $00, $00, $00, $80

BASIC_POINTERS_SIZE = * - BASIC_POINTERS

.SEGMENT "MAIN"

; entry point which does an RTS, so it works right from BASIC's SYS command

.PROC main

; initialize SID

jsr init_sid

; initialize screen

jsr init_screen

; show title screen

jsr title_screen

; restore screen

jsr restore_screen

; put the BASIC loader into BASIC program memory

lda #<BASIC_LOADER

sta $fb

lda #>BASIC_LOADER

sta $fc

lda #<BASIC_LOADER_ADDR

sta $fd

lda #>BASIC_LOADER_ADDR

sta $fe

ldy #0

loop1:

lda ($fb),y

sta ($fd),y

iny

cpy #BASIC_LOADER_SIZE

bne loop1

; update the BASIC pointers for the new BASIC program just copied

lda #<BASIC_POINTERS

sta $fb

lda #>BASIC_POINTERS

sta $fc

lda #<BASIC_POINTERS_ADDR

sta $fd

lda #>BASIC_POINTERS_ADDR

sta $fe

ldy #0

loop2:

lda ($fb),y

sta ($fd),y

iny

cpy #BASIC_POINTERS_SIZE

bne loop2

rts

.ENDPROC ; main

With those two problems solved, the user can cleanly exit the game and then jump right back in, with no load time, regardless of whether the game is in cartridge or disk form. It’s not earth-shattering or anything, but I think it’s pretty cool.

Closing Thoughts

I had a lot of fun doing this project, and learned quite a few things. It was neat to revisit something I wrote so many years ago, and to breathe new life into it. The game won’t win any awards, but that’s okay. If you download and the play the game, or look at the code, and have any questions about how I did this or that, feel free to ask. If you have any suggestions on how I could have done things better, I’d love to hear about that too.

Leave a Reply